The Monstrous Bestiary

@MonsterBestiary

Fascinating facts about the #monsters of #myth, #legend, #folklore and pop culture! Curated by me, Jamie Lee. Tweet me and suggest a monster for me to cover!

You might like

Welcome to The Monstrous Bestiary! My name is Jamie, and I'm looking forward to researching and sharing fascinating facts about my favourite monsters from myth, legend and popular culture. I'll cover one monster for a while, then move on to another. Let's get started! 😀

It's believed that the fastitocalon, aspidochelone, lyngbakr and other 'monster islands' were invented by ancient fishermen to explain real phenomena such as pumice rafts or 'vanishing islands' - islands that are exposed at low tide but submerged at high tide.

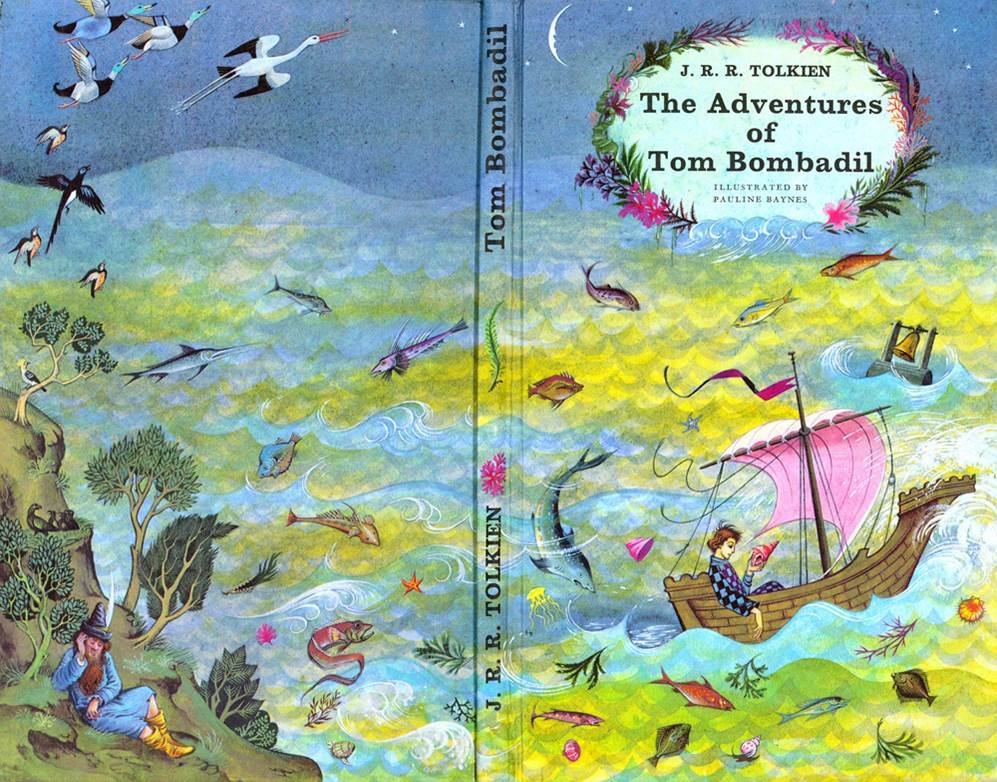

A later Old English translation of the Physiologus renames the aspidochelone the 'fastitocalon'. This is the name J. R. R. Tolkien chose to use when the monster appears in 'The Adventures of Tom Bombadil'. This places an ocean island monster in the legendarium of Middle Earth!

The aspidochelone isn't the only fantastical creature described in the Physiologus. Others include the phoenix, sirens, ass-centaurs (!) and unicorns. It also mentions the ichneumon which, as we discovered back in May, is a mongoose from which the cockatrice 'evolved'!

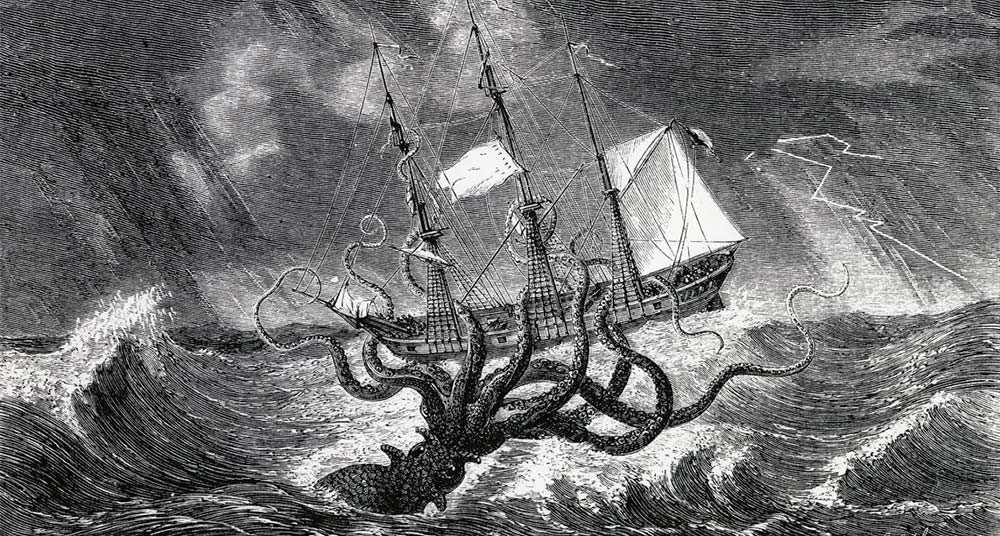

In the Physiologus, the aspidochelone is used to deliver a Christian lesson. Tying your ships to the monstrous 'island' is like getting tied up with the Devil - in both cases you're going to get dragged down to a terrible fate (though not necessarily the one depicted here).

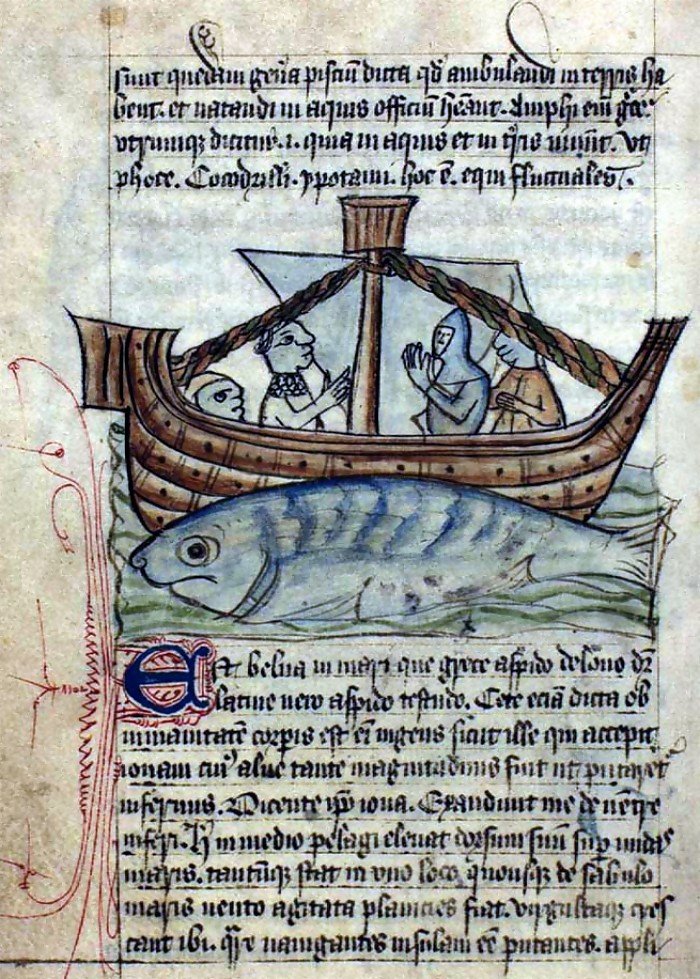

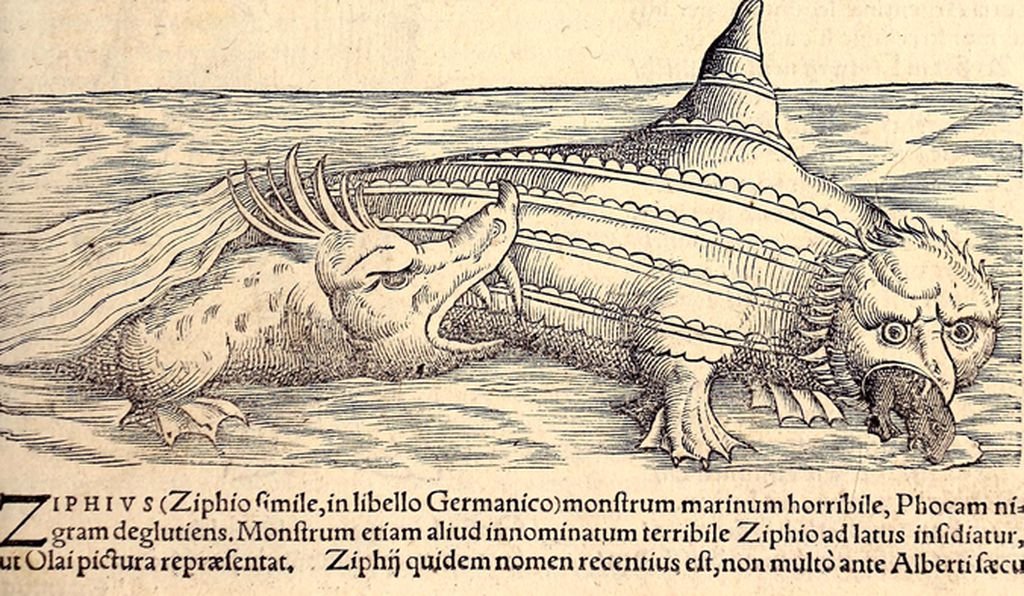

The Physiologus seems to be a little confused concerning the genealogy of the monstrous aspidochelone. The name itself means 'asp-turtle', suggesting something reptilian, but the text describes the creature as a 'great whale'.

It's believed that both the lyngbakr and the kraken (originally named the 'hafgufa'!) are based on the same even older monster - the aspidochelone. This monster was first mentioned in the Physiologus, a 2nd century Christian text by an unknown author.

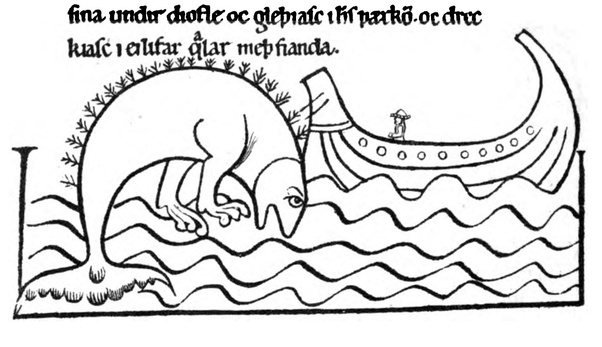

The lyngbakr is described in a 13th century Icelandic saga as being the biggest whale in the ocean, with a back covered in heather that can be mistaken for an island. When a crew landed on the island the lyngbaker would dive, drowning the unwary sailors.

The first reference to the kraken being mistaken for an island occurs in Erik Pontoppidan's 'Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie' (1752), but he may have been confusing the creature with another Scandinavian island monster - the even bigger lyngbakr.

Land ahoy! Or is it? It's time to explore the mysterious interior of MONSTER ISLANDS. No, not islands populated with monsters Dr Moreau style - islands that actually ARE monsters! If you thought the kraken was the only legendary giant of the ocean, guess again...

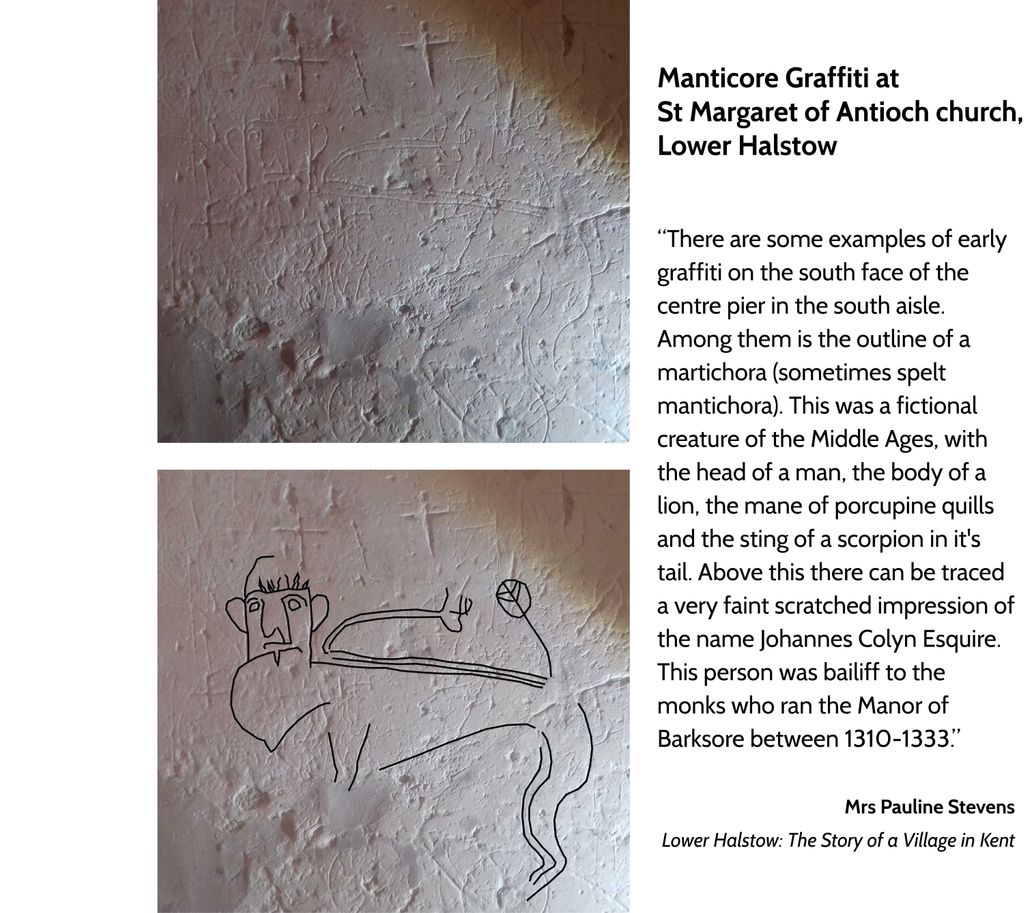

I'm delaying the monster islands series to bring you this fascinating example of medieval manticore graffiti! Many thanks to church warden of Lower Halstow, Christopher Mayes, for providing the details and photograph, and to @TheSacredIsle for pointing me in the right direction.

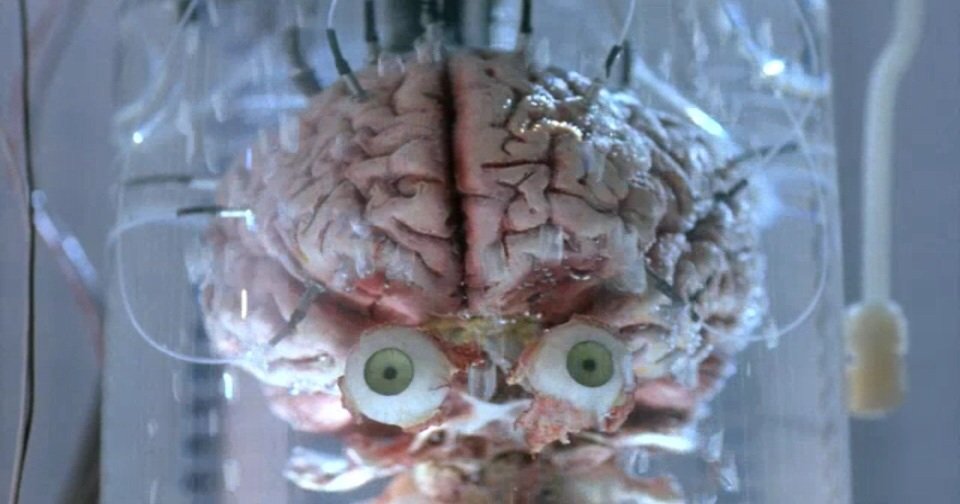

I don't believe Monster In My Pocket ever made a disembodied brain figure, so here's Dr Braindrain from the P.E.T. Alien collection instead. Our foray into more modern monstrosities is now at an end. Next we return to myth and legend with a brand new series on MONSTER ISLANDS!

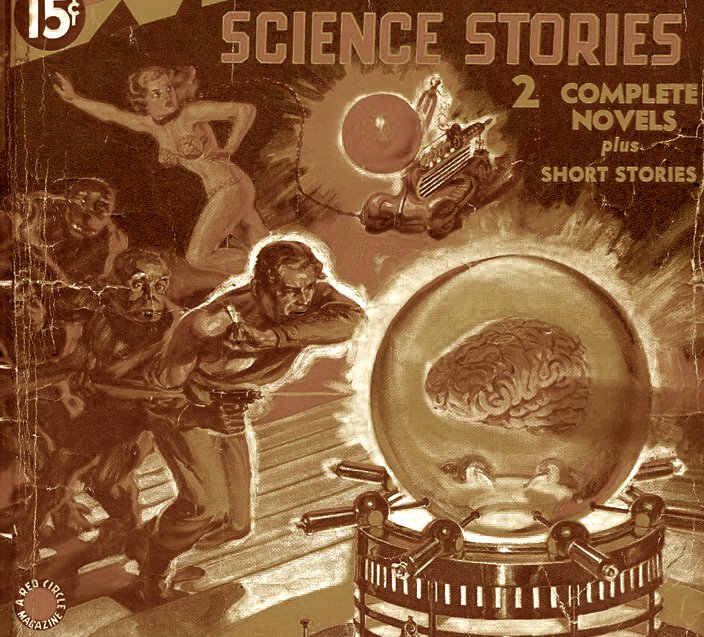

There are countless TV shows, movies and comics featuring disembodied brains. Why do we find them so mesmerising? My theory is that they're symbols of our anxieties concerning a lack of control and agency, despite our intelligence and the growing collective knowledge of mankind.

Let's play 'spot the basilisk'!

Lots of fun heraldic beasts here including a mantyger, unicorns and Azathoth who gnaws hungrily in inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond time and space amidst the muffled, maddening beating of vile drums and the thin monotonous whine of accursed flutes.

The ‘Scots Roll’ may be the earliest surviving armorial to have been produced in Scotland itself. Totalling nine pages, it illustrates 114 arms belonging to the Scottish nobility (Add MS 45133, ff. 46v-50v). ow.ly/7GZT30kpWYw #IAD18

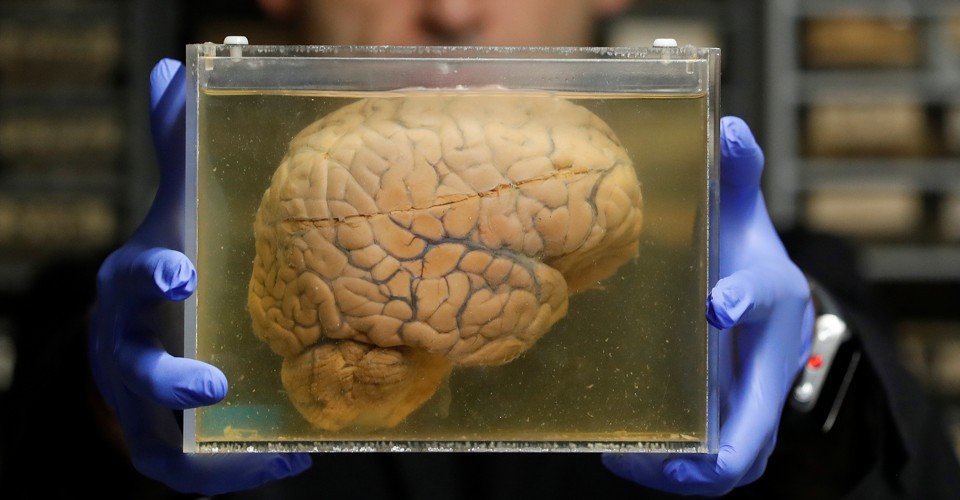

The brain in a jar isn't just a sci-fi cliché - it's also at the centre of a fascinating philosophical debate about perception, self and transhumanism. I recommend this 2017 article in The Atlantic for an entertaining and informative look at the subject: buff.ly/2JiLrD5

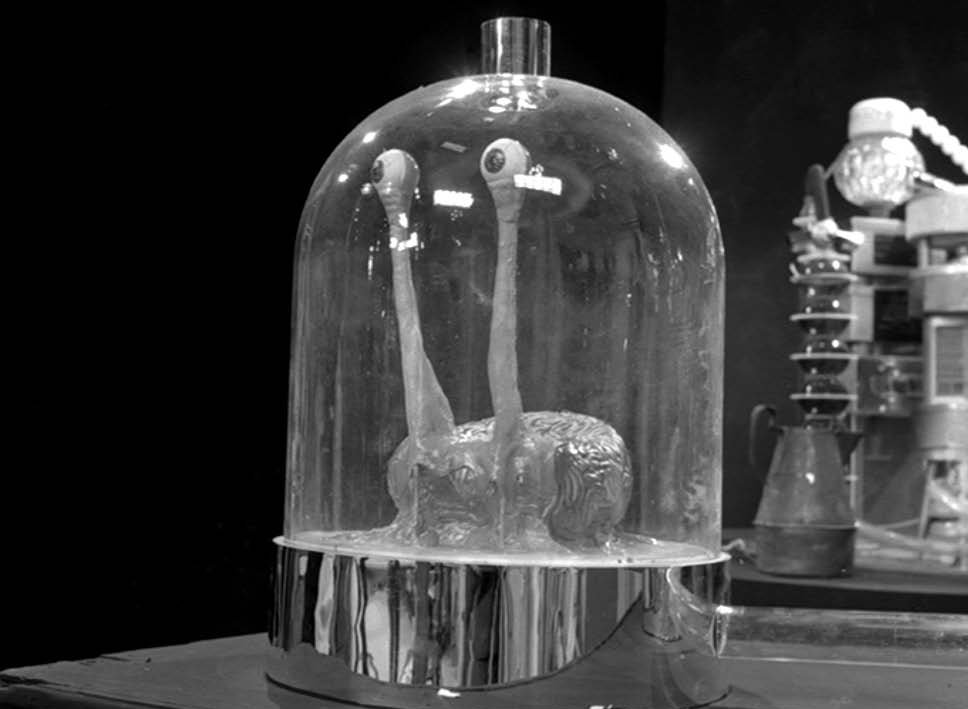

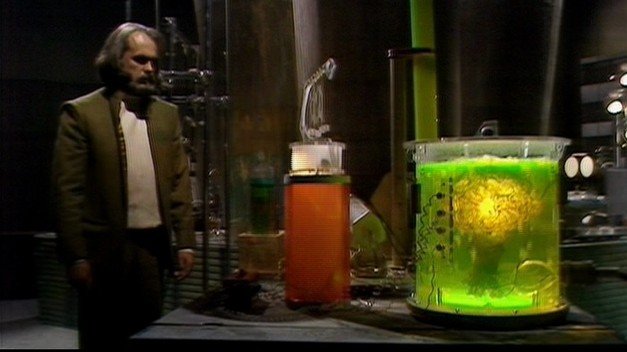

Disembodied brains have featured as antagonists throughout the long history of sci-fi classic Doctor Who. Such creatures appear in the stories 'The Keys of Marinus' (1964), 'The Brain of Morbius' (1976), 'Planet of the Ood' (2008) and 'The Return of Doctor Mysterio' (2016).

Misreading the Mokele-Mbembe (the Mokele-Mbembe, Part 1) By @TetZoo blogs.scientificamerican.com/tetrapod-zoolo…

Another influential example of disembodied brains in literature is Lovecraft's 'The Whisperer in Darkness' (1931), although in this story the living brains are the victims of the true monsters - the Mi-go, an extraterrestrial race of fungoid creatures and their god Nyarlathotep.

Ulbach was the first to write about disembodied yet living brains, but far from the last. Another early example occurs in Gustave Le Rouge's 'Le Prisonnier de la Planête Mars' (1908), which depicts a once-powerful Martian civilization now ruled by the malevolent Great Brain.

There was a lot of disembodied brain stuff happening in France in the 1800s it would seem. In 1887, Jean Baptiste Vincent Laborde made the first recorded attempt to revive the heads of executed criminals by connecting the carotid artery of the severed head to that of a dog.

United States Trends

- 1. Miami 198 B posts

- 2. #TheTraitorsUS 15,7 B posts

- 3. Carson Beck 27,5 B posts

- 4. Hail Mary 4.681 posts

- 5. #PeopleWeMeetOnVacation N/A

- 6. Natty 21,5 B posts

- 7. Porsha 2.463 posts

- 8. National Championship 34,8 B posts

- 9. Malachi Toney 8.876 posts

- 10. #CFBPlayoff 14,7 B posts

- 11. maya hawke 13,3 B posts

- 12. Chambliss 12,9 B posts

- 13. The U 839 B posts

- 14. Bruno Mars 54,2 B posts

- 15. #FiestaBowl 11 B posts

- 16. Portland 186 B posts

- 17. Michael Irvin 7.194 posts

- 18. #DigitalBlackoutIran 27,3 B posts

- 19. I Just Might 49,1 B posts

- 20. Oreshnik 77,9 B posts

Something went wrong.

Something went wrong.